Are your participants being dishonest in your research?

/One of the challenges we face as researchers is to obtain honest and accurate responses. Unfortunately, people do not always provide accurate answers and they sometimes intentionally give you dishonest answers. They do so for many different reasons but two are most relevant with respect to research.

One of the reasons people lie is social desirability bias. We want to shed positive light on ourselves. Think about the last time you visited doctor’s office and were asked “how many times do you exercise per week?” Or “how many alcoholic beverage do you consumer per week?” Did you feel the urge to round up the number of time you exercise and round down the number of drinks you consume? Well, I do (but at least I’m being honest about my dishonesty now!). And I know most people do, too, even though it’s in our best interest to be honest and convey more accurate information to our doctors.

Another reason is for self-interest. For example, people lie on tax forms and insurance applications to benefit themselves. For example, you might say on the form that you are non-smoker. When probed, you might admit that you smoke “occasionally” or that you quit last Monday…

This poses a great challenges for researchers who study behaviors that are prone to dishonesty.

So how can behavioral science help you obtain more honest answers?

One team of researchers, including my colleague Dan Ariely at Duke University, conducted a simple, yet brilliant study. Their participants were invited to a research lab and asked to solve a set of math problems. They were paid additional $1 for each correct question. So, it was to their advantage to solve more math problems. Or should I say, it was to their advantage to claim they solved more math problems?

They all, however, had to sign that the number of correct questions they were reporting was to the best of their knowledge and believed it was correct and complete.

At the end of the sessions, they self-reported the number of correct responses to collect payments. Researchers were of course secretly keeping track of who’s been honest and who’s not.

Here’s the results: In one group, 37% of the participants cheated to get paid more, and in another group, 79% cheated to get paid more.

What made such a huge difference between these two groups? The first group signed at the top of the form and the second group signed at the bottom of the form. Therefore the first group signed before they self-reported the number of correct responses, and the second group signed after they filled out the form..

The researchers argued that the participants in the first group were more honest because the morality was more salient in their mind.

So, if you have any forms that people have to sign to swear that they’ve been honest, be sure to bring it to the top of the form. But what if you don’t have a custom to do so? You still can elicit the morality without having them sign.

Let’s review another experiment.

College students were invited to a research study that consisted of two supposedly separate questionnaires administered together for efficiency. Unbeknownst to the participants, these questionnaires were related and, in fact, the first questionnaire served as a primer to elicit the concept of honesty in one group but not in another (care was taken so that students wouldn’t be suspicious, e.g., different font and format were used for each questionnaire and the data showed that students weren’t suspicious at all).

The first questionnaire contained a vocabulary task.

Here’s what it looked like for participants in Group A:

|

Which of these words are most closely related to the word “common”?

1. Blend

|

Here’s what it looked like for participants in Group B:

|

Which of these words are most closely related to the word “honest”?

1. Open

|

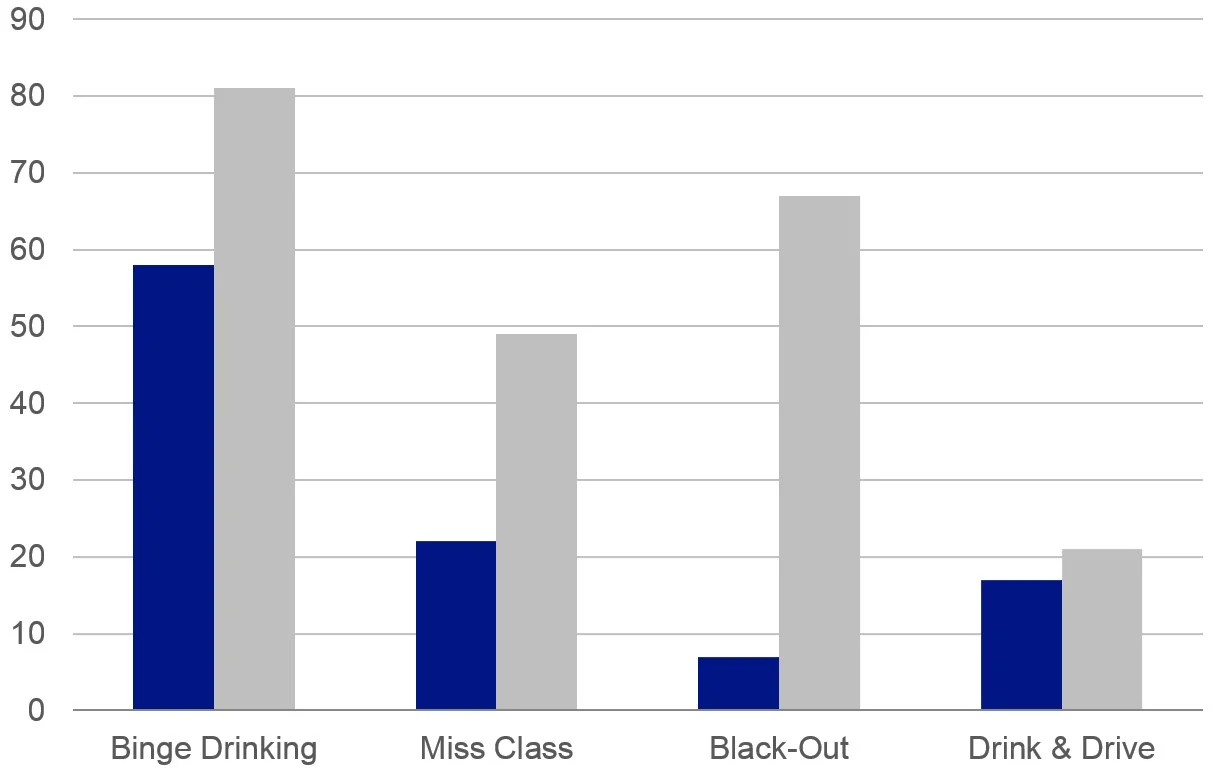

After they had completed several of these, the researcher left with the questionnaire and another researcher stepped in with a different questionnaire. This time, the questionnaire was the same for the both groups and it was about their drinking and its related behaviors. In particular, they reported whether or not they had ever 1) engaged in binge drinking (e.g., 4-5 or more drinks in one sitting), 2) missed a class due to a heavy drinking the night before, 3) had a black-out due to heavy drinking, and 4) driven under the influence.

Here’s the percentages of people reporting to engage in those behaviors in Group A (blue bar) and Group B (gray bar):

Why might have this happened? It’s because the concept of honesty was made salient among participants in Group B through the word tasks called priming in the first questionnaire, and the salience of the honesty carried over to the second questionnaire even though students didn’t think these two questionnaires were related. This is why students in Group B were more likely to honestly report socially undesirable behavior.

This study demonstrated that we can increase honesty by simply activating the concept of honesty, even in an unrelated task.

So, how can you elicit more honest responses in your survey work?

If you usually have people sign at the bottom of the form/questionnaire to swear their honesty, then consider moving it to the top of the form. If you don’t have such custom, can you implement it?

If that’s not a possibility then explore what other ways you could elicit the concept of honesty. For example, can you have your participants do the honesty vocabulary task before your questionnaire?

Or is there any other visual or audio cues that communicates honesty?

Whatever priming method you’d apply, be sure to do an experiment (e.g., randomized control trial) to test the effectiveness. Otherwise you’d never know if/how your method is effective.

Another important thing to be aware is to keep your survey short. If it’s too long, the concept of honesty would fade away by the time they complete the questions.

Do you have any priming ideas you’d like to test with your next projects?

If so, contact us at namika@sagaraconsulting.com. Let’s see if we can get your participants to be more honest!

If you are interested in taking our online course on behavioral economics for market researchers (partnering with Research Rockstar), click here.

Interested in learning more about how to apply behavioral economics to market research projects?

Or, check out our online course on behavioral economics for market researchers (PRC eligible)!

References:

1. Shu, Lisa L., et al. "Signing at the beginning makes ethics salient and decreases dishonest self-reports in comparison to signing at the end." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109.38 (2012): 15197-15200.

2. Rasinski, Kenneth A., et al. "Using implicit goal priming to improve the quality of self-report data." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 41.3 (2005): 321-327.